Urban Archaeology's work at Gloucester Cathedral gets a name check in a new paper on archaeological recording in the digital age. Colleen Morgan and Holly Wright’s paper ‘Pencils and Pixels: Drawing and Digital Media in Archaeological Field Recording’ explores the history of archaeological field drawing, exploring how the process of looking and drawing contributes to archaeological understanding and interpretation. From this position of understanding they then consider whether digital (paperless) field recording and drawing can deliver the same benefits.

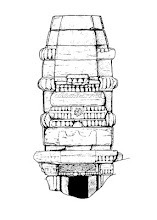

| Digital elevation of Gloucester Cathedral Lady Chapel during repair work. |

In the paper our work at Gloucester Cathedral is used as an example of a hybrid system, where traditional drawn recording is fused with digital recording (in this case photorectification) in order to get the best from each technique. As Colleen says in the paper, experienced archaeologists have an awareness of the uses and benefits of a wide range of digital and non digital techniques, and can move (hopefully) seamlessly between them, understanding how they interact.

It’s a great paper and well worth trying to get behind the paywall to read, and has led me to jot down a few thoughts on digital/traditional recording.

Digital recording has been around for some time, but its use is rapidly accelerating, replacing hand drawn records almost completely at some British archaeological companies. The decisions on adopting technology and digital recording should only ever be taken once you have a thorough understanding of the benefits and pitfalls, not least how the technology enables better, rather than just quicker and cheaper archaeological recording. There are also issues of de-skilling, especially problematic when technology is only used by a few, rather than all the Diggers on site.

With any recording

technique there are the technical aspects -accuracy, precision, clarity, speed,

utility, cost, archive compatibility- of the process and end product to

consider, but there is also a large element of 'seeing' which can be missed in

any analysis of the benefits of traditional/digital techniques. Quite simply the

process of traditional drawing and recording makes you look, think and decide,

constantly. This is sometimes referred to as ‘interpretation at the point of

the pencil’: drawing close up at scale makes you think about what you are

seeing in a way 1:1 tracing on an i-pad, or dGPS recording someone else’s

sprayed-up features cannot. It adds a

separate, additional layer of thought and understanding into the process of

recording, whereas a reliance on digital techniques can create a ‘point and

shoot’ attitude where the subject is not looked at it in the same detail, or recording

is delegated to a specialist who has no knowledge of the contexts they are

recording.

In my mind it is crucial that the recording of a subject’s attributes is done

at the same time as the recording of its surface. So if we create a 3D model of

a building, we have to also sketch/plan/annotate to record how it fits together

whilst in front of that building: looking and peering and prodding, constantly thinking

about how it all fits together. The 3d model is not actually a full record

until it has these attributes, it is just a surface, a picture, an image.

Without the attributes of context, boundaries, materials, context relationships

etc it is nothing but a whizzy toy to show clients. Unfortunately for us

archaeologists these attributes need to be recorded in front of the subject,

not back in a warm office!

Potentially there needs to be more attention paid to the differentiation between techniques that have replaced traditional drawing where you are basically using a different 'pencil' (such as a TST or dGPS), and techniques which are fully 'automated' surface records (3D modelling, Structure Through Motion, Photorectification) where the interpretation of the surface is removed from the point at which recording is done and often carried out some time later by a different archaeologist.

The process of planning can be speeded up by using a TST or dGPS instead of hand planning huge swathes of site, but it must be remembered that this can affect the recording quality: although more accurate, it is often less precise, as if the site is planned at 1:50 rather than 1:20. Not every line on a drawing is equal.

The process of planning/drawing, using a key and line conventions, automatically forces you to attribute as you go. You interpret and attribute at the point of the pencil, constantly re-evaluating what you are recording. With remote automated techniques you don't, there is too often a separation between the image, and the interpretation/attribution, and the 'chain of integrity' is broken. It’s like you record a stone by stone multi-context plan of a series of metalled layers and spreads, but don't decide/draw the boundaries until you are off site. It can be, essentially, just making up a record. The process of drawing is one of decision making, and should be valued.

The

answer in my mind is using appropriate techniques in the appropriate place, and

quite often using a hybrid traditional/digital approach. This is nothing new,

for over a decade many archaeologists have hand planned their individual

features, but located them using digitally captured Drawing Points, picked up

by dGPS. This allows detailed recording where needed, but rapid recording where

it is considered not so vital. The techniques dovetail well and allow the

excavator to carry out all the important recording, interpreting as they

record, and feeding their thoughts back into the interpretation and record.

Different recording techniques are used in different situations, some digital,

some traditional, as the paper says ‘When it is not feasible to employ

the full range of archaeological recording methodologies, the true expertise

may be in knowing when to deploy different approaches.’

Colleen has written a short blog on the paper:

The paper is behind a

paywall, but for those with access it can be found at Morgan, C., & Wright,

H. (2018). Pencils and Pixels: Drawing and Digital Media in Archaeological

Field Recording. Journal of Field Archaeology, 1–16