|

| Anne Baynham's memorial following cleaning |

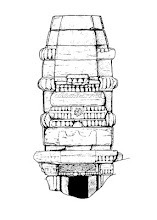

A rare example of a 17th century effigial memorial to a

newborn baby has been relocated at Holy Trinity church, Minchinhampton in the Cotswolds. The memorial was rediscovered high up in the north transept when the organ was removed for repair. Following fundraising by the Minchinhampton Local History Group the memorial has been cleaned and moved to a new position in the west end of the church by Mark

Hancock of Centreline Architectural Sculpture, where it sits alongside a good collection of medieval and

later memorials.

|

| The memorial is now displayed in the church narthex |

Urban Archaeology has been recording and

researching the monument pro bono for MLHG and the church as part if its wider research into the church which was published as a new book by Hobnob Press last month.

The 18th century antiquarian Ralph Bigland recorded that the

memorial was located in the chancel and that it included the Baynham arms

(Frith 1990, 6523). When the nave, aisles and chancel were demolished by Thomas

Foster in 1842 the memorial was re-erected high up in the north transept where

it was soon obscured by the organ.

The monument was broken and clumsily repaired in 1842; to

aid reconstruction the stones of the courses were numbered on the back from '3'

through to '9', with courses '1' and '2' missing. Setting-out marks and rebates

in the top of the memorial confirm there was an additional tier, presumably the

Baynham arms of course no '2'.

|

| Details of the reverse of the memorial showing location of setting-out lines, painted numbering and repair |

The effigy is carved from English alabaster and bears traces

of gilding and paint. It depicts a recumbent female infant whose proportions

suggest an age of 2–3 years old but is dressed as an adult. She is wearing a

plain coif with an ornately decorated cap over, a cloak, and a high-waisted

nightdress with a finely gathered wide ruff. There are four strings of beads

around her neck. Her right hand rests on a skull which sits on a cushion, and

she holds a (now broken) palm leaf in her left hand. The girl is depicted

largely immune to gravity, almost levitating within the cartouche, although the

carving is lifelike especially in the arms and hands with their chubby fingers

and there is considerable detail on the depiction of her clothes.

|

| The effigy, carved from English alabaster |

Anne was the fourth daughter of Joseph Baynham and Alice

Freame. Alice was born and lived at nearby Lypiatt Manor then part of Stroud

parish, and which lies across the Golden Valley from Minchinhampton. There are

no other Baynham or Freame memorials in Holy Trinity.

Joseph and Alice were forty two years of age with three

young daughters when they lost the newborn Anne. They lived at a time when

child mortality was high, as was maternal mortality, and they would have

personally known many families who had lost one or more children, or mothers in

childbirth. Our modern sensibilities must be acknowledged when we look at

Anne’s memorial, and whilst the desire to memorialise the death of any family

member can be readily understood, the context of such desires and thoughts were

potentially very different in the 17th century.

The memorial to Anne, although not of the very first order,

would have been an expensive item requiring payment to the church and to the

mason and sculptor and for carriage and fixing. Careful thought would have

accompanied the decision to commission the alabaster effigy which would have

been ordered, carved and then shipped from its workshop and fitted into the

Painswick Stone surround before being fixed in place on the north wall of the

chancel. Decisions would have been made -by the family or the sculptor- about

the representation of the deceased, and the exact iconography employed

including the dress, the open eyes, palm frond and the skull memento mori.

It is intriguing that Anne is not portrayed as a newborn

baby but as a toddler or young girl wearing the fashionable and high-class

clothes of the time. In the medieval and Tudor periods babies and children were

represented on memorials in a variety of ways and the family would have been

aware of ‘weepers’ and of ‘chrysom’ representations of swaddled babies on

memorials in the churches they attended. It used to be thought that chrysom

effigies represented children who died within a month of their baptism and

would be buried wearing their baptismal robe, but the effigies may also be a

representation of an older infant (Oosterwijk 2000, 55–6). Many representations

of swaddled infants are simple, however they could be more ornately carved: the

alabaster memorial to Edmund Brudenell †1590 in Stonton Wyville,

Leicestershire, includes a swaddled baby lying on a table beside the deceased (Lee

and McKinley 1964).

Dr Sophie Oosterwijk has examined the representation of

children in medieval and renaissance memorials, from the appearance of

anonymous ‘weepers’ below and beside the main characters, and when the deceased infant is

portrayed as older than their actual age at death. As well as being dynastic

statements, Oosterwijk suggests that portraying a deceased male infant as an

adult may be an attempt to idealise them at the ‘perfect age’ of Christ when he

ascended to Heaven, whilst a female infant would be idealised at the age of the

Virgin Mary at Annunciation, thought to be between twelve and fifteen (Oosterwijk

2010). Anne is of course not portrayed as a virginal teenage bride, but as an

infant of high status.

‘Child monuments and the inclusion of offspring as

weepers may indeed often have been inspired by dynastic considerations, but

this does not preclude the idea of affection for children and heartfelt grief

at their loss. It is true that there was a very real risk of death at a very

early age, and parents were aware of this. However, it would be wrong to assume

that children were neither loved nor remembered. Even the anonymous rows of

offspring on monuments suggest that every child counted’ Oosterwijk 2010,

59

The portrayal as a toddler may also be due to the family’s

imagining of Anne living on in the afterlife, and growing up to be as her three

elder sisters, then aged six, five and three, and the elaborate dress including

a cap as worn by a married woman may be used to indicate wealth and class.

Anne’s portrayal as an older infant may also be linked to the religious belief

that Anne was one of the 140,000 virgins of the Apocalypse, by the 16th

century the scope of the Holy Innocents or ‘first fruits’ had expanded to include all

children who died before the age of seven. Dr JL Wilson lists several memorials

that reference this belief although many of these are depicted as ‘not dead but

sleepeth’ (Mark, v, 39) rather than open-eyed like Anne. The palm frond,

held by Anne, is a sign of the Holy Innocents but Wilson states that this is

most frequent in slightly older children, rather than the very young who were

universally agreed to be included in the Holy Innocents (1990, 57–8). Roses

were also used to depict virginity at this period, and it is possible Anne is

holding a rose or a lily for purity, although the foliage looks more

frond-like.

‘One of the commonplaces of the treatment of children in

recent works has been that children were seen as intrinsically evil, needing

correction to be saved. The evidence of tomb-sculpture brings this into

question. There is no doubt in the imagery of these tombs that the children

commemorated are, while inevitably mortal, saints. Both the rose and the palm

symbolise their innocence; the palm triumphally, the rose with a softening

consciousness of their earthly life. Their grieving parents are comforting themselves

with a vision of their children as among the Holy Innocents’ Wilson 1990,

62

|

| The left hand holds a broken palm frond |

In light of this societal religious belief the epitaph is of

interest, and compared to some similar monuments is relatively understated and

matter of fact. The first half simply describes the parents and their lineage,

the second part is about Anne but it does not dwell on her innocence, or her

place in Heaven. God has simply taken her from pain to joy, but there is a

simple admonition to the reader that we are all to die, and should

therefore watch, pray, repent and forsake sin, but be happy when the day comes

to join God for eternity.

A comparator to the effigy is provided by the effigy of

Thomas Hewer †1617

in Emneth, Norfolk, at the foot of a part of a larger canopied tomb to his

parents. The alabaster effigy of young Thomas reclines asleep, his head rests

on a pillow partially concealing a skull. Thomas’s hair is gilded, as is detail

on the cushion. The Hewer memorial was by the sculptor Nicholas Stone and cost

£95, of which only a small proportion would have been for the child’s effigy

(Norfolk Churches).

Anne’s effigy is in bas relief rather than freestanding

but also has great similarities to those of Lionel and Dorothe Allington (1638)

in Bottisham, Cambridgeshire, where the two children recline (more

realistically than Anne), and the elder child rests their hand on a skull on a

cushion and holds a rose. The pose is almost identical.

There were accomplished sculptors producing high-quality

effigial sculpture in the county at this period, the best known local sculptor

of the early 17th century is Samuel Baldwin, who is often described

as being originally from ‘Stroud’ but was actually from Lypiatt, moving to

Gloucester around 1620. Baldwin produced work of the finest quality for the

most affluent and well connected families in the county and was their

pre-eminent sculptor in the early 17th century (Gray 1964).

Baldwin’s work would have been known to the Baynhams as he

had earlier produced a monument to the pirate Henry Brydges (†1615)

in the nearby Avening church, and of course his works at Gloucester cathedral,

but also as he was a local Lypiatt man. Many fine works have been ascribed to

Baldwin’s workshop, and there is no doubt that he was often first choice for

the best families producing the very finest memorials.

Dr Adam White has kindly commented that the main inscription

panel could well be from the workshop of Samuel Baldwin, with a similar panel on

the monument to Giles Savage (†1631/2) and his family at Elmley

Castle, although White cannot see a real comparison in the effigy with

Baldwin's work which may have been provided by another workshop. Despite

his importance and relative prominence as a sculptor the work of Samuel Baldwin

is relatively undocumented and is in need of further research, the work of

lesser regional workshops is even less well understood.

|

| Detail of the inscription showing inlaid pigment |

Further research is needed into the English funerary

alabaster workshops of this period to establish whether this was a unique

sculpture or was an established model, and whether a particular school or

production centre can be suggested. The outer monument is typical of

locally-produced work (perhaps by Baldwin’s workshop), whilst the effigy may be

imported from out of county. The quality of the carving is good, but not of the

very highest standard, it is however both detailed and well executed, with lifelike

carving of the subject despite the ‘anti-gravitational’ posture and slight

stiffness of some parts of the subject. The memorial is included in the new book on Minchinhampton church, available from the church or from Hobnob Press.

Thanks

to all at Minchinhampton Local History Group, Holy Trinity church, and to Mark

Hancock and his team at Centreline Architectural Sculpture who carried

out the move. Thanks also to Rev. Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, Dr Sophie Oosterwijk, Caroline

Stanford, Alison Taylor, Dr Adam White, and Dr J L Wilson who generously

provided additional examples of memorials to newborns and recommendations for

reading which have all benefitted this article. The interpretation of their

papers -and any mis-interpretation- is however all this authors!

Frith, B (ed) 1990 Ralph Bigland Historical,

Monumental and Genealogical Collections relative to the County of Gloucester,

Part Two: Daglingworth–Moreton Valence, Glos. Record Series 3

Gray, ID 1964 ‘A 'Forgotten Sculptor' of Stroud,’ Trans.

Bris. & Glos. Arch. Soc. 83. 148–9

Lee, J M and McKinley, R A 1964 'Stonton Wyville', in A

History of the County of Leicestershire: Volume 5, Gartree Hundred, London British

History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/leics/vol5/pp308-312

accessed 25 April 2025

Norfolk Churches http://www.norfolkchurches.co.uk/emneth/emneth.htm accessed 29th April 2025

Oosterwijk, S 2000, ‘Chrysoms, shrouds and infants on

English tomb monuments: a question of terminology?’ Church Monuments

(Journal of the Church Monuments Society) 15, 44–64

Oosterwijk, S 2010 ‘Deceptive appearances: the presentation

of children on medieval tombs’ Ecclesiology Today 43 December 45–60

Wilson, J 1990 ‘Holy Innocents; Some aspects of the

Iconography of Children on English Renaissance Tombs’ Church Monuments 5,

57–63