Urban Archaeology’s Chiz Harward is to record the world-famous Great Cloister at Gloucester Cathedral as part of a major conservation project

|

| Gloucester cathedral's Great Cloister is the earliest surviving fan vault |

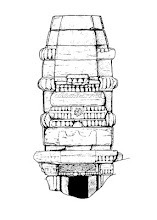

Gloucester Cathedral’s Great Cloister is one of the most significant and beautiful works of English medieval architecture and is known through film and dramas to millions around the world. It is also an incredibly important archaeological site both as the earliest surviving fully-developed fan vault and as it contains evidence for at least two earlier cloisters on the site.

Following a successful trial in 2022, work has started on a long term project to conserve the 14th century Great Cloister which is suffering from a variety of threats including inappropriate hard Portland cement pointing, decay of the stone from salts and the weather, chemical pollution, decay of the stained glass, and a roof that is largely made of RAAC – reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete. Working their way around the cloister the cathedral’s own masons will clean the walls and vault, remove the cement and replace it with breathable lime mortar, and carve and fix new stone.

Cathedral Architect Antony Feltham-King notes that ‘the Great Cloister has long been on the schedule for major conservation attention and it’s time has come. This is our generation’s opportunity to carefully un-pick mistakes made in the past, and to hand it on to our successors in good order.’

|

| The tracery is in need of conservation to preserve the cloisters for the next few hundred years |

Cathedral Archaeologist Richard Morriss said ‘the Cathedral has been studied architecturally for several centuries and dozens of books and articles have been written about it. It has become clear that detailed recording of even the smallest pieces of archaeological evidence can lead to a greater understanding of the way the Cathedral and its various components were put together – and an understanding of how the forgotten masons of the past dealt with the challenges that faced them on what was then the leading edge of architecture and design.’

|

| To date, attention has largely focussed on the visual appearance of the cloister, but how was it built? |

‘The sheer beauty and symmetry of the cloister’s fan vault calms and beguiles the observer but behind the surface treatment of intricately carved ribs and trefoils there is a solid structure that has never been properly studied. The cloister has to be seen as an integral part of the rebuilding of St Peter’s abbey in the new Perpendicular style -an architectural style that was developed right here by its highly skilled masons.

‘With this vault the abbey’s masons were working out new ways of building -true fan vaulting had probably never been tried before, anywhere. If you look behind the tracery there is a very complex structure of shaped blocks transferring stresses and forces through the walls. This approach does not seem to be repeated in later fan vaults suggesting that the masons may have been playing safe as they innovated, drawing on the experiences gained during the reinforcement of the south transept and the near-contemporary work to refashion the Quire and Presbytery. St Peter’s masons developed Perpendicular architecture as a visual style, but the work here is also structurally audacious and groundbreaking.’

|

| The underlying structure of the vaulting is picked out by the grey Portland cement pointing |

Work probably started on the Great Cloister almost immediately after the Black Death, and there are signs that it’s massive loss of life may have impacted on both the supply of stone to the project, and the skillset of the banker masons who carved the stones - if not the vision of the master mason who led them. One objective of the project is to see how the construction of the cloister developed over the decades it took to build, as the masons learnt how best to construct these extraordinary structures.

Locked away within the masonry are the remains of earlier cloisters, with blocked doorways and reused stonework from the Norman cloister and scorched stones bearing witness to cataclysmic fires. There are also tantalising glimpses of the 13th century cloister with the ‘stiff leaf’ foliate capitals of the northeastern door hidden behind its Perpendicular successor.

‘That is classic Gloucester’ says Chiz ‘rather than build a new doorway the masons added a façade in front of the existing one -look behind and it is all still there. We see this approach throughout the Perpendicular rebuilding, from the south transept to the tower, Quire and Presbytery. Was it to save money? Possibly also to limit disruption, but it is also part of a signature approach: the comprehensive re-presentation of existing buildings to give them a radical new appearance in an economic way.’

|

| Evidence for an earlier Norman arched doorway survives behind later blind tracery |

Chiz has worked on projects at the cathedral since 2016 and is looking forward to unpicking the story locked away in the stones and mortar. The detailed archaeological recording is expected to rewrite and rebalance the history of the Great Cloister, but also the earlier cloisters and the buildings that surrounded them; setting the cathedral’s cloister in its medieval monastic context; and shining further light on the masons, and monastic community, that designed and built these remarkable buildings.

The cloister will remain publicly accessible throughout the project, with a walkway beneath the scaffold as the team works its way around the cloister over the coming years. Initial generous funding of the works has come from the Headley Trust. Read more and follow the project on the cathedral website: https://gloucestercathedral.org.uk/cathedral/projects/the-cloister-project