MOLA have just published the Roman monograph on their major

urban excavations at Plantation Place, City of London. I worked on the

main excavation in 2000, when there were around 70 archaeologists working on site, and over

the next three years with smaller teams excavating pile positions, sewer shafts

and monitoring groundworks and piling. At the end of it all, after several

years of excavation, assessment and analysis, I ended up writing the chapter on

the post-Boudican reconstruction fort, a 'find' that still ranks as the best

I have ever made.

|

| The MOLA monograph, copyright MOLA |

I had wangled my way out of the office to go and work on 'Plantation',

a huge site in the heart of the City that was being redeveloped by British Land,

who funded all the archaeological works. It was a welcome relief to be on site

again, digging, after a long winter inside checking paperwork from the Spitalfields

excavations of the year before. The area supervisor, Phil Treveil had to go in

to finish work on No1 Poultry, another massive site excavated a few years

earlier, and I ended up looking after his area until the end of the site.

The stratigraphy on any urban site is often chopped about

and fragmented by modern foundations, but at Plantation not only did we have

large square concrete pad foundations from the 1930s building, but service runs

between the pads had further divided the stratigraphy into a large number of fairly isolated islands of survival. Joining

these up in post-excavation would be a major task, and the systematic recording

of the stratigraphy was vital to allow comparison between contexts only a metre

apart, but completely separated. It was tough, and with only a very few experienced

staff on my area there was a lot of running around giving advice, explaining

and generally getting things moving.

The basement slab had horizontally

truncated the archaeological deposits, removing all medieval and post-medieval

horizontal deposits, and much of the later Roman sequence too. Cut features,

cesspits and cellars had punched through the stratigraphy, and gave 'windows'

onto the earlier sequence, really useful when trying to make sense of the 3-D

puzzle of layers, fills, cuts and masonry that surrounded us and which we were

gradually unpicking.

First theories

It was one such 'window' that first suggested there was

something 'new' on site; an 18th century cesspit had been emptied by Bridget,

and we then started taking out the brick lining so she could plan the cut. With

half the lining removed I swapped to a trowel and started cleaning up the newly

exposed section, the clear profile of a 'V' shaped ditch was revealed cutting

through the natural from near the base of the sequence.

'This could be really

important' I said: 'the eastern boundary of the early Roman settlement; it's

meant to run along somewhere near Mincing Lane', a road only a few dozen metres

away. To my south another supervisor, Ken Pitt, had seen a similar ditch, and

for a while we worked on this initial hypothesis that this could be the early pomerium or civic boundary to Londinium:

a legal and physical boundary that marked the edge of the town.

The fort emerges

As the site progressed and we dug deeper, the islands of

archaeology gradually merged and we began working on larger and more contiguous

areas. East of the ditch we started noticing organic stains -the remains of

timbers that had rotted long ago; as we went deeper the stains were better

preserved and we could see that they formed the parallel 'stripes' of a horizontal

timber structure, some of them partially charred. In the section there were

several of these layers, and between them were not only layers of mud-brick

debris -some scorched- but also what looked to me like mineralised turves,

complete with soil profile and a dark stain where the grass had been. The whole

sequence was lain on a gravel surface and was only found west of that initial

ditch. To the south Ken's team found another ditch, farther out than the first,

and we had found a second one too, curving round to the west. So it wasn't the

town boundary, but what was it?

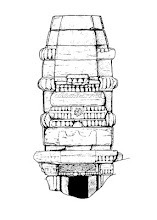

We had a pair of parallel 'V' shaped ditches, with so-called

ankle-breaker cleaning out slots. These ran straight for much of the length of the

site, but then gradually curved to the west. Inside the ditch was a sequence of

layers of turf and re-used mud bricks, lain between a series of horizontal corduroys

of timbers, with vertical stakes driven through this mass.

It looked like a

defensive rampart, but I knew next to nothing about Roman defences. I called

over Trevor Brigham, who was running the site, and ran through what I

thought, he seemed to think it possible, and the next day he brought in a book on

Roman forts and we went through, checking what we had against the textbook. It

all matched.

Finding the fort led to a re-assessment of what had already

been dug on site: it became clear that many of those isolated islands of

archaeology were actually part of the rampart, and that the corduroy had already

been excavated further west, where it had been interpreted as a collapsed

timber fence. We had the north east corner of a Roman defensive circuit, and it

dated to after the Boudican revolt of AD 60/1. As the site progressed more

details slotted into place as we excavated and tested the hypothesis: a

granary, a latrine, and a cookhouse set into the rampart's inner face. It all

fitted and it all worked.

Finding and recording the fort's physical remains was only

the start of detective work that pieced together evidence from archaeological

sites, classical sources and which confronted long-held ideas of London's

archaeology and history. It involved looking through all the adjacent excavation archives to

try and find where the southern and western ramparts lay, and it meant learning

all about Roman military defences, Boudica, and the political aftermath of her

revolt.

Dating the fort

The fort's date was initially problematic -it clearly post-dated the Boudican

revolt as it overlay the burnt remains of the settlement she destroyed, but how

much later? We felt there was a growing case for the fort to be part of a

concerted military reconstruction in AD63 -a date provided by new evidence of

military water-lifting engineering from Blossom's Inn and the military-built

waterfront at Regis House.

The evidence fitted together: a new waterfront with timbers

bearing the stamp of a Thracian cohort, whilst fragments of a leather tent, and

military items were found in dumps behind the revetment. Reconstruction work appeared

to have been carried out across Londinium, but the dates didn't all fit. The

new dendro dates said AD 63, but the accepted pottery dates were later - AD 70,

dated by the advent of a particular type of pottery, Highgate C. For a while we

were stuck. We had sherds of Highgate C from our rampart, but it seemed to be

earlier.

The answer came from looking at surrounding sites. We

realised that there were two phases of activity, the first a military-led

reconstruction of infrastructure starting in AD63, whilst the second phase -the

Flavian boom- came a few years later. Before they knew there was a fort, archaeologists

had believed that there was a lengthy hiatus after the revolt and had lumped

together the two phases into one, now we could show that there were two phases

and picking apart adjacent sites they suddenly made more sense.

Function and political context

The post-Boudican fort should primarily be seen as a base for

the reconstruction of Londinium; the garrison itself was probably largely based

in leather tents, with troops stationed at Plantation Place reconstructing the

essential infrastructure of the town. Across Londinium there is evidence for

clearing of ruined sites, and the military re-establishment of roads,

waterfronts, warehousing and water-supply/drainage, anticipating the civilian

redevelopment of Londinium, as well as outer defensive perimeter works. In the

event the full reconstruction of the town had to wait a few more years until

the 'Flavian boom' of the AD70s, but there is clear evidence that the military

were involved in extensive reconstruction work, and that their base was at the

Plantation Place fort.

As a statement of political intent it is unequivocal,

and fits with the known political events following the Boudican Revolt where the

classical sources tell us that after the defeat of Boudica the Roman forces of

Suetonius Paulinus exacted a terrible revenge, but a new approach was taken

after Nero sent Polyclitus to lead a commission of enquiry. It was at this

point that we believe that the Plantation fort was built, a base from which

Londinium could be re-established, potentially as a new capital.

As archaeologists we often get asked 'what's the best thing

you've ever found', and for many of us it will be a complete pot, a burial with

grave goods, or in rare cases something gold, but for me I can honestly say

that uncovering the fort at Plantation Place was the best thing I have ever

found. It was a discovery that unfolded over days, and then months, and into

which the more work you put, the more you got out. To discover a fort is one

thing, but Plantation Place was more; working with that team of Diggers, we

found something that changed our understanding of the re-birth of London, and made me realise the unique contribution archaeology can make to history.

No comments:

Post a Comment