My work as an archaeologist has often involved both receiving

and giving on-site training, from a brief chat about how to record a context

to a structured training session on stratigraphy or Roman building

techniques. Training and development is central to every archaeologist; every

project is different and there is always something new to learn, and that is

one of the things that makes archaeology such a fulfilling and fascinating

discipline. Training provision and Continuing Professional Development,

although core to the profession, has been neglected and can often be reduced to

Health and Safety courses such as First Aid at Work or CAT and Gennie, rather

than specific, ongoing training in carrying out the day-to-day role. Over the

last few years I've been working on how to change this, to make training

available to all staff, at the place of work, and throughout their careers.

|

| Training site staff: clay tobacco pipes. photo LP Archaeology |

Whilst working at MOLA about ten years ago I independently started

developing training materials for site staff -simple one or two page handouts

for use in archaeological 'toolbox talks' given to the whole site team, or as

the foundation for more focused one-to-one mentoring and training. The

materials were made available as free downloads, and later led to work

providing training materials and sessions for archaeological companies. My

interest in training combined with an involvement in Diggers' Forum (a

campaigning group within the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists) and led to

research into how we provide, and document, training and CPD for the many, not just

the few; something that paralleled and echoed work by several others including

the now hugely successful BAJR Skills Passport.

Looking into how archaeologists are trained, it was clear

that there were real problems with training provision at all levels, and that these

problems had been known for some time; however there had been little work on

how to change this situation. At one level there seemed to be a mutual blame game

between universities and employers as to who should train new entrants (for

example see papers given to the 2012 FAME Forum). Although some university

departments, such as Winchester, offer a solution to this conundrum by providing

courses designed for those intending a career in professional archaeology.

Several industry schemes offered possible routes out of the

training impasse, but nearly all were focussed on the individual, not the team:

the IfA developed a series of Workplace Learning Bursaries with its partners, but these largely

addressed the needs of a few fortunate individuals, rather than the majority of

staff. The bursaries did reportedly change the way the host organisations thought about

training, but there is little evidence that they improved training for their

rest of staff, and certainly there was no flood of companies stepping forward

to fund their own bursaries. The NVQ in Archaeological Practice is another scheme that has so

far failed to achieve its potential, although the related development of the

National Occupational Standards for archaeology has created a useful framework

for archaeological training schemes, especially when seeking to tap into funding

sources for apprenticeship schemes from the Department of Business Innovation

and Skills. These apprentice schemes have great potential in providing individuals

with new ways into the profession, with funded, structured, on-the-job training

and the development of apprenticeships has the possibility of helping train

existing staff through the development of training materials and techniques.

Individual employers have also developed schemes; Cotswold

Archaeology developed a set of 'Designate' schemes, for Supervisors, Project Officers

and Project Managers, training and supporting existing staff into new roles.

Whilst I worked at Cotswold Archaeology I developed a series of training

sessions and materials that were given to all staff, not just designates, part

of a commitment to training that went beyond the individual.

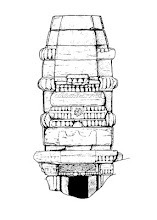

More recently I worked with LP Archaeology on their year-long

100 Minories site; there we provided training on a two-prong approach: LP ran a

series of pub-based 'Symposium' sessions with speakers on a wide range of

topics related to the site, whilst I embedded training into the working day,

with inter-active site tours, talks from visiting specialists, discussions on specific

artefacts and buildings, as well as more structured training sessions on aspects

of site-work ranging from matrices, photography and paperwork checking through

to clay pipes and bricks.

My research and practice has led to a firm belief that training should be available for all staff, not just the fortunate or pointy-elbowed, that training should be available at the place of work, linked to the work wherever possible, and that training is a mutual commitment that requires work from employer and employee. I developed the idea of a Training Hour, intended to deliver this training on site, at minimal expense or time cost, and to change the training culture into a positive one rather than a tick-box CPD scheme.

The Training Hour is intended to be a mutual commitment to

provide/receive roughly an hour a week of work-related training. This can be

provided by site colleagues or visiting specialists, by an interactive site

tour, by one-to one mentoring or training, or Toolbox Talks. Short, bite-sized

chunks of training that can be related to both the site and the team. Once

training is embedded into the working week it can finally become a mutually valued and fundamental part of the

job, and stop being seen as a chore or irrelevant, but as a way of becoming a better

archaeologist.

For more on the Training Hour concept see Training Diggers and Changing Cultures: Embedding a ‘Training Hour’ within the Working Week, published in The Historic Environment, Vol. 6 No. 2, September 2015, 167–76