Urban Archaeology has been working at Gloucester Cathedral over the

last couple of years, both on Project Pilgrim

and as part of ongoing repair and conservation work on the exterior of the Lady

Chapel. Recently we’ve also been working a bit further from the main cathedral

buildings in a quiet corner of the precinct and turned up a surprising survival

of the monastic past.

|

Monument House and St Mary’s

Gate, looking east towards the precinct

|

We’ve just completed a watching brief on the refurbishment

and alteration of Monument House, a Georgian townhouse situated next to the

medieval St Mary’s Gate on the western side of the cathedral precinct and once

the gateway to the River Severn from the Benedictine Abbey. Monument House is a

very fine example of a Georgian townhouse and dates from about the 1760s. Although it is in the cathedral precinct Monument House faces west, out towards

the river and the old docks (the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal would not be

completed until 1827).

Monument House is part of the Cathedral estate and is being

extensively refurbished internally and externally and a 1960’s extension is

being replaced. The refurbishment work provided an opportunity to inspect the

house, whilst the demolition and construction works meant that there would be

an archaeological watching brief wherever any excavation was required for the

new extension.

Working closely with contractors Town and City Builders Ltd

Urban Archaeology monitored the excavation of the courtyard area behind

Monument House. As was expected archaeological deposits survived across the

area and despite its limited size, the excavation provided excellent evidence

for the development of the rear courtyard of Monument House, with flagstone and

brick floors, outhouses and drains dating from the 18th century through to the

20th century.

|

| Overhead view of external courtyard area showing flagstone floors of external buildings; scale 1m and 0.5m |

What was less expected was the discovery of a masonry

channel right at the bottom of a new footing trench. The culvert walls were built

from Lias and limestone blocks and it measured 1m wide internally; although it

had filled up with soil, probing showed it was at least 0.68m deep. The channel

had later been covered over with a continuous brick vaulted roof and remarkably

this was intact along most of the length of the footing trench. The culvert

still presented serious problems for the new foundation (which was due to run

along the side of the vault) as it was too weak to carry the new extension, and

the culvert was largely an empty void, further weakening the area.

|

| The north wall of the channel, with brick vaulting roof; the brick structure at the right of the picture is a Georgian silt trap that feeds into the culvert; scale 0.5m |

The Fulbrook Stream

The Fulbrook Stream was the main monastic ‘grey’ water

supply which was used to flush through the drains and toilets in the monastic

precinct; it was an existing watercourse that was diverted into the precinct in

the early 12th century and channelled around the northern precinct before

exiting just north of St Mary’s Gate and presumably running down to the Severn.

The masonry channel we found is a bit to the south of the expected line of the Fulbrook

Stream but is almostly certainly the main Fulbrook channel at the point just before it exited the medieval monastic precinct, presumably

through an opening in the precinct wall.

Parts of the monastic water supply and distribution system

are known from across the precinct, and parts of the water channels have been

found in the past at Millers Green east of Monument House. There appears to

have been a ‘dendritic’ system of drains and channels, small drains feeding

into larger ones, and eventually into the main channel, with this being the

main channel.

The various conduits, channels, tanks and culverts of the

water supply and distribution system would have been maintained throughout the

medieval period and after the Dissolution the water system continued in use

with repairs to conduits at the Bishop’s Palace in 1604–1607 and later repairs

are also known. By 1761 however the system of channels was not in good order

and was recorded as being ‘offensive to the inhabitants within the precincts’

and it was ordered that it be cleansed ‘and

a floodgate or wall erected at the place where the stream had been diverted’ cutting

off the Fulbrook at the point where it had previously been diverted into the

precinct.

The culvert appears to have been retained at the time Monument

House was constructed in the mid 18th century and its foundations carefully

avoided damaging the culvert roof. Monument House is known to have been built

by the 1760s when it was occupied by a Mr Keyse, and may therefore predate the

apparent abandonment of the old monastic water supply in 1761. Parts of the old

water system were probably retained after the blocking off of the Fulbrook, as

channels would have still been needed to carry away the large volumes of water

collected on the roofs and hard surfaces of the precinct. As this was the last

point on the system it is likely that Monument House utilised the culvert to

dispose of its waste water and we excavated the remains of Georgian brick

silt-traps and drainage systems that fed into the culvert.

Send in the machines…

|

| Feeding the cable for the crawler down the culvert |

|

| View up the culvert showing brick vaulted roof springing off the masonry walls |

Having established what the culvert was, we needed to find

out how long it was, and for all we knew the culvert might still run with water

during periods of high rainfall. With only small holes in the brick vault it

was impossible to see far down the culvert so the Cathedral called in Three Counties Drain Services

who were replacing drains at the other end of the Cathedral precinct (also with

an archaeological watching brief, but that’s another story…). They brought

their remote control crawler unit, equipped with a directional camera, which trundled

up the culvert whilst we watched on a closed circuit TV screen and measured out

the cable…the crawler found the west end of the culvert had been bricked up at

the street frontage, whilst the east end was cut through by a nineteenth

century extension of the adjacent Community House. The culvert was therefore

‘dead’, but what next to do?

Bubbles, grey bubbles…

|

| Foam concrete being pumped in to fill the culvert, the black membrane is to protect the surviving archaeological deposits |

The usual

method for dealing with a void beneath a footing would be to infill it with

stone, and compact the stone so it could carry the foundation, however this

would collapse the culvert and there was no way of getting stone into the

culvert without extensive archaeological excavation and the destruction of the

culvert roof.

The solution was to use aerated ‘foam’ concrete, pumped into the culvert to fill the void and support the ground above, whilst also forming the base for the footing, with a redesigned raft foundation. Foam concrete is structurally strong, but can be removed easily if required at a later date, so technically the concrete infilling was reversible, and the archaeological deposits and structures were protected by a ‘terram’ geotextile membrane.

The solution was to use aerated ‘foam’ concrete, pumped into the culvert to fill the void and support the ground above, whilst also forming the base for the footing, with a redesigned raft foundation. Foam concrete is structurally strong, but can be removed easily if required at a later date, so technically the concrete infilling was reversible, and the archaeological deposits and structures were protected by a ‘terram’ geotextile membrane.

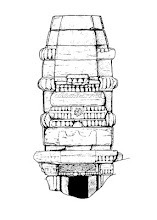

Internal works

|

West wall of basement, this is probably part of the monastic precinct wall;

scale 0.5m

|

The refurbishment also gave an opportunity to inspect the

interior of Monument House; the basement is made up of conjoining barrel

vaults, although the front and north wall of the basements are in stone, the

front wall being probably the remains of the medieval precinct wall.

|

Pegged timber studwork with brick infill, and original

timber detailing and stair; scale 0.5m

|

Many of the internal walls are of timber studwork, fixed together with timber pegs, with brick nogging or infill between the timbers. Some of the timbers are clearly reused, including a massive medieval oak beam used to span a wide doorway on the ground floor. There are clear keying marks on the studs, made with an axe to aid keying to the plaster. Much of the original timber detailing survives in good condition, including panelling, skirting, cupboards with original hinges, and the stairs and banisters.

|

Axe marks for keying plaster to the studwork

|

The new plastering is being done in traditional lime materials

and the building will retain all its Georgian character. Externally the roof is

being re-slated and areas of damaged brickwork are being repaired and repointed

by Town and City Builders Ltd.

The discovery of the culverted Fulbrook Stream channel helps

illustrate the extent of the buried archaeology and history beneath the

cathedral precinct and the potential for discovering further details of the

development of this fascinating part of Gloucester. The careful recording and

mapping of these archaeological discoveries not only helps tell the story of

the site and wider precinct, but also helps inform future work and allow us to

understand its potential impact.

The combination of archaeological recording above and below

ground added greatly to the understanding of the development of the site, and

highlighted the interaction between ‘standing buildings’ and archaeological

deposits: there is no divide between the two.

The discovery of the culvert was perhaps unexpected,

although archaeological deposits were expected and planned for. With all

contractors working closely together and with advice from Andrew Armstrong,

City Archaeologist, this unexpected discovery was dealt with quickly and with

limited interruption to the construction programme.

No comments:

Post a Comment