A

recent contract with LP Archaeology in the City of London raised some aspects

of recording worth some thought. The contract was an archaeological evaluation

on a site that straddled the projected line of the Roman, medieval and

post-medieval ditches that lie immediately outside the walls of Londinium and

London. Due to the expected depth of the archaeological deposits (geo-technical

boreholes showed up to 7.8m of potentially archaeological strata) the

evaluation strategy was for five 2.5m x 2.5m test pits that would be dug as

fully shored shafts. The test pits were located to give information on the

survival of archaeological strata, the nature of any such deposits, and the

potential survival of complex masonry and environmentally significant remains.

The pits were positioned across the site in an L-shape with three of the test

pits located to provide an east–west transect across the expected line of the

defensive ditches.

In

order to illustrate the excavated sequence it was decided to record a

representative section of each test pit, these could be used to construct an

illustrated section across the site which would illustrate the strata found in

the test pits, along with their conjectured extent. The impact of the proposed

development could be mapped against this to give an immediate visual

representation of the site. Unfortunately given the projected depth of the test

pits they would need to be close-shored with steel trench sheets and

timberwork. After the first metre or so of each pit had been dug and the shoring

had gone in, there would be little opportunity to view and record a traditional

section as due to the loose nature of the fill the trench sheets needed to be

dropped every 200-300mm to ensure the integrity of the shoring*.

|

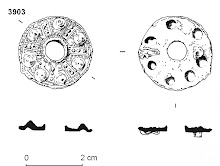

View of Test Pit 3 at approximately 7m depth

|

A traditional section drawing was recorded for the top 1.2m of each pit, and the section pins located on the top plan, however a different technique had to be used for the next few metres of the dig. The pits were excavated by hand and recorded using the MoL Single Context recording system, this involved drawing a 1:20 plan of each significant context, complete with levels, breaks of slope and hachures as appropriate. Every context had as a minimum a sketch plan with levels and measurements. The section could therefore be reconstructed from the plans as we dug: the extent of each context was simply mapped onto the section from the plan, with the relevant levels fixing the vertical height. Breaks of slopes could be similarly mapped onto the section drawing and the line of the slope added –joining the dots- as the context was being excavated. Cuts presented a slightly more complex situation, however a combination of the levels, planned extent, and the written description of the break of slopes, sides, and base, along with the sketched profile on the back of the context sheet meant that cuts too could be reconstructed with a good degree of accuracy.

Each context

was added to the section immediately after it was planned, which meant that the

section drawing could act as a quick reference on our progress, and highlighted

trends in the deposits –such as the transition from horizontal external

deposits to sloping levelling dumps reflecting the underlying slope of the

ditch sides.

|

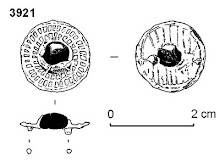

South facing section of Test Pit 1, reconstructed from plans

|

The final

sections, recording 7.8m of stratigraphy, provided a clear representation of

the strata, albeit slightly simplified. The individual test pit sections were

then scanned, digitised, and geo-referenced into a GIS project onto which

conjecture and the proposed development impact was added.

|

South

facing section of Test Pit 3, the top 1.2m was drawn traditionally, the

remaining 6.6m reconstructed from plans and levels

|

The exercise

proved to be highly successful and was of great use on site, as well as

providing the basis for informative illustrations in the evaluation report. The

technique of reconstructing sections from plans raises wider issues about the

strengths of single context recording, and the need for accurate planning and

levelling.

One common

criticism of Single Context recording from rural archaeologists is that

sections are ‘never’ recorded. This is of course not true: Single Context

allows you to record as many sections as you like, wherever you like, the fact

is that many urban archaeologists choose not to ‘automatically’ section

everything because they prefer to dig stratigraphically rather than by section.

On complex archaeological sequences (and to be perfectly honest on simple ones

too) digging in plan is usually far more successful than knocking a slot or

section through an area and relying on the section to illustrate the sequence. You

allow the stratigraphy to work itself out, rather than imposing a pre-conceived

interpretation on the sequence and hoping you get the section in the right

place. Sections do of course have a fundamental place as part of the repertoire

of recording techniques, especially recording the interfaces between dynamic or

reworked contexts, however their use in an urban context is generally limited

for good reasons.

In

addition to the advantages of digging in plan, there is a further reason why

sections are not religiously used: the method outlined above can be used to

reconstruct a section between any two points on a site so you don’t need to

record sections as with proper recording they can be reconstructed along the

best line. Using the planned extents the horizontal extent of the context can

be fixed on any transect, the levels provide the vertical height value, and the

breaks of slope and hachures, along with the physical description and profile

drawing allow more complex cuts and interfaces to be recorded.

This

does of course rely on good recording, in particular it reinforces the need for

accurately located levels, and for the taking of sufficient levels to

illustrate the surface of any context. This is a Good Thing. A single level located on a plan should indicate that the surface of the

deposit is uniformly flat, whilst some deposits, cuts or structures may need

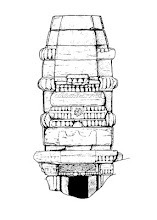

tens of levels to accurately allow the context to be properly recorded. The photo below is of the plan of a barrel vaulted structure, there was insufficient time

to draw a profile in addition to the plan before the trench was backfilled,

however it is possible to reconstruct a profile across the vault due to the

accurate planning and the correct distribution of levels.

|

| Recording the barrel vault |

|

Accurate plan of barrel vault with levels, enabling reconstruction of profile

|

Accurate

planning is essential for all archaeological recording methods, however in SC

recording it is additionally crucial that plans and levels are accurately

recorded as it is the superimposition of plans that demonstrates the

archaeological sequence via the plan matrix, and hence the creation of the

stratigraphic matrix. Accurate planning and levelling, whether on permatrace or

a measured sketch, can also allow any mistakes in excavation to be corrected:

if you dig a context out of sequence, or overdig it, then as long as you have

accurate plans/sketches and levels you can always get yourself out of the hole

you have dug. The use of ‘safety levels’ –additional levels taken in case the

original extent of a context is incorrect- is another way of making sure that

the true plan can be reconstructed should the context not pan out as originally

thought.

A

related issue is that of the nature of the interface between contexts, for a

few years my interest in recording systems has led me to feel that the generic MoLAS-derived

context sheet can be improved by a few simple additions. A key missing prompt

is, I believe, to record the interfaces between contexts, and the nature of the

surface of the context. This prompt exist on some company’s context sheets,

such as Cotswold Archaeology, however it should be added to everyone’s sheets

in my view! The nature of the surface and the interface between contexts –is it

trampled, is it diffuse- is essential part of the record and a key way of

understanding a sequence and the formation processes at play. In the 1980s the

Inner London Archaeological Unit used a variant of SC recording where each

deposit was given two context numbers: one for the surface of the context, and

one for the ‘body’ of the context. It may be over-recording, however it did

work in highlighting the need to record the interface between contexts. The

need for, and use of, prompts on context sheets is probably worth a separate

essay, but without specific prompting many archaeologists forget to properly

record contexts, and the nature of interfaces between contexts is one area that

is consistently under-recorded.

The

creation of reconstructed sections is one method in the archaeological toolkit,

and a very useful one when your section proves to be in the wrong place, but it

also underlines why proper accurate recording is so important if we are truly

to preserve by record, and how all the different elements of the drawn and

written record work together to create a true record of both each context, and

the entire site.

*It is

of course possible to create a running section of the exposed 2–300mm of

section as work progresses, however this can be time-consuming as you need to

constantly set up new string lines. It is certainly more accurate and allows

details of the inclusions to be recorded in detail, and is probably the better

method if the sequence is of complex structural remains such as clay and timber

buildings. In this instance the expected nature of the deposits: levelling

dumps, tips of refuse and external soils, meant that the reconstructed section

was a suitable form of record and accurate enough to reconstruct these ‘bulk’

deposits. As with all decisions about the suitable level of recording there are

alternatives, there is not a simple solution that is always correct. The

important thing is to always think about what you are recording, how you are

recording it, what the record will be potentially used for, and then to make an

informed decision.

No comments:

Post a Comment