We can tell a lot about the medieval buildings on our site at

Horse and Groom Inn from the physical remains that survive, but there are also

other clues to the appearance of the buildings, some of which can be inferred

from what is not there, rather than

what is.

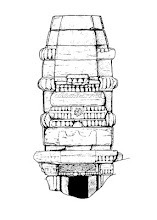

Ten rooms make up our medieval building complex, forming two

wings around a courtyard. Most of the walls are substantial –up to 0.8m wide

and survive up to 1.3m high. They are built of local stone, with a foundation

course of large stones at the base of each wall, and roughly coursed stones

above. The walls are bonded using clay rather than lime mortar, an odd choice

given that in the medieval period there was a large limekiln a few hundred

yards uphill from the site.

The thickness of the walls suggests that the buildings were solely of

stone construction rather than timber frames set on low stone walls, although

some rooms may have had one or more timber framed stud-walls or partitions. Medieval

documents relating to Bourton-on-the-Hill describe stone walls up to 3.6m high

(12 foot), enough for a lower-ground floor with first floor above.

|

| Part of the medieval buildings showing blocked doorway and substantial partition walls: these rooms were terraced into the hillside and there may have been a first floor above; scales 0.5m and 1m |

The doorways would have had wooden doorframes set into the

walls, with the wooden doors mounted on iron hinges or pintles. The walls would

have been bare stone –no fragments of medieval wall plaster have been recovered

from the site. The walls may have been limewashed internally although no trace

survives.

The buildings would have had timber roofs, fixed with wooden

pegs and roofed with thatch or possibly wooden shingles. No fragments of Cotswold

stone roof tiles have yet been found and although these expensive tiles would

have been removed for reuse it is hard to believe that none would have been

broken and discarded in and around the site. Similarly no earthenware tiles

have been found on the site. Medieval documents record that some buildings in

Bourton were roofed in stone tiles by the 14th century, but thatch

was also used in the village.

The buildings had a variety of floor surfaces –fragments of

stone flags indicate that some rooms were paved, in others just the underlying

soil, bedrock or clay, whilst another had a floor of trampled stones. Scorch

marks on some floors show that there were fires in the rooms, although only one

formal hearth was found. Scorch marks on some walls suggest fire damage, whilst

many stone blocks are partially scorched indicating they were reused from a

building that had burned down.

The best-known Cotswold ‘deserted medieval villages’ are

made up of a series of low earthworks formed when the buildings’ walls slowly decayed

and collapsed to form low mounds. On these sites the individual building groundplans

can be made out from the earthworks and whole villages can be mapped from the earthworks

without the need for excavation.

At our site there were no such earthworks: before excavation the hillside was

a gradual slope, and there were no visible mounds or depressions from the buried

walls and rooms. The reason why only became apparent as we excavated: it is clear that

the site was actively cleared and the buildings were all deliberately

demolished, probably all at the same time. Someone clearly made a decision to

raze the site to the ground, we don’t as yet know why but there may be a clue

in the detailed records kept by Westminster Abbey who held the manor in the medieval

period.

At first the buildings were cleared of anything that could

be reused: the internal fixtures and fittings were ripped out and the stone

flags were ripped up, the roof covering removed, and the roof timbers taken for

reuse. The walls were then demolished working down from the wall-plate. Most

walls were carefully dismantled –the inner and outer skins of facing stones were taken away for

reuse whilst the smaller and less valuable rubble from the wall core was thrown

into the centre of each room. As the walls were demolished downwards, so the discarded

rubble rose upwards, and the demolition ceased when the two met leaving a flat

level surface that gradually grassed over to leave no visible trace of the buildings.

Why the buildings were demolished may never be known, but it

does tell us something about the end of the life of the complex. The materials

from the buildings were carefully selected and taken away for reuse –this demolition

did not happen at a time when there was no market for good building stone or when there was

no labour available to move them; someone in a position of authority and with available resources made a decision, and the end of this

site may have been part of the beginning of a new building or farm. Once we

have fully recorded the walls we will dismantle the stones and they will be

piled up for reuse in the new site, for some of the stone blocks that will be

their third incarnation.

No comments:

Post a Comment